Report: Russians do not evade sanctions using crypto says Chainalysis

Report: Russians do not evade sanctions using crypto says Chainalysis Report: Russians do not evade sanctions using crypto says Chainalysis

What many have suspected, but was difficult to actually prove, has now been confirmed by crypto cybercrime experts Chainalysis: There is no evidence, whatsoever, that sanctioned Russian entities are using crypto to evade sanctions.

Cover art/illustration via CryptoSlate. Image includes combined content which may include AI-generated content.

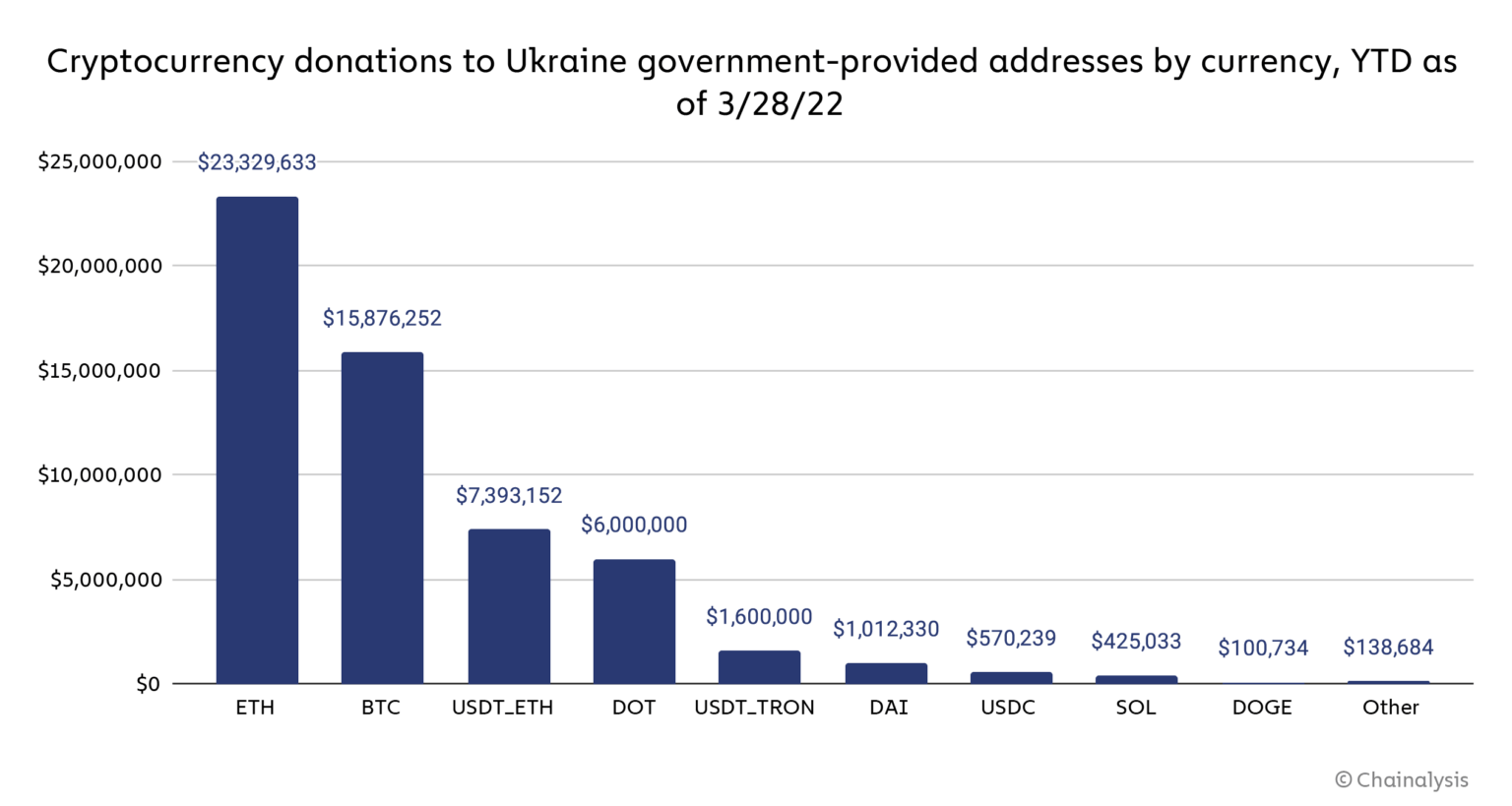

As Russia’s war in Ukraine continues, cryptocurrencies are taking on an important role in the conflict, but not in the capacity of evading sanctions on Russian entities or oligarchs. On the contrary, crypto has proven itself to be very useful in supporting Ukraine as users around the world have donated over $56 million in cryptocurrency to addresses provided by the Ukrainian government alone.

This is “showcasing not just the crypto community’s generosity but also virtual assets’ unique utility for cross-border payments,” Chainalysis report on the matter reads.

As most readers know, the United States and many of its allies in the EU and elsewhere have taken unprecedented actions against Russia, including adding Russian oligarchs, their family members, and their businesses, as well as all major state-owned banks and many energy exporters, to the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (OFAC) Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons List (SDN).

Western powers have also removed select Russian banks from the SWIFT system, essentially cutting them off from the global financial system, and sanctioned Russia’s central bank, preventing it from using its $650 billion in reserves to mitigate the impact of the sanctions.

There’s no evidence sanctions evasion is happening

Many are now wondering how Russia’s business and political elites could use cryptocurrency, such as bitcoin (BTC) or ether (ETH), to evade sanctions. “While there’s no direct evidence this is happening, It’s a reasonable concern as Russia accounts for a disproportionate share of several categories of cryptocurrency-based crime, and is home to many cryptocurrency services that have been implicated in money laundering activity,” the report reads.

As Chainalysis co-founder Jonathan Levin explained while testifying before the U.S. Senate, if cryptocurrency-based sanctions evasion is happening, it would probably look more like typical money laundering activity, in which relatively small amounts of cryptocurrency are moved gradually to disparate cashout points, rather than all at once in huge transactions.

Chainalysis’ report goes on to list the different ways sanctions could be evaded and dismisses all of them.

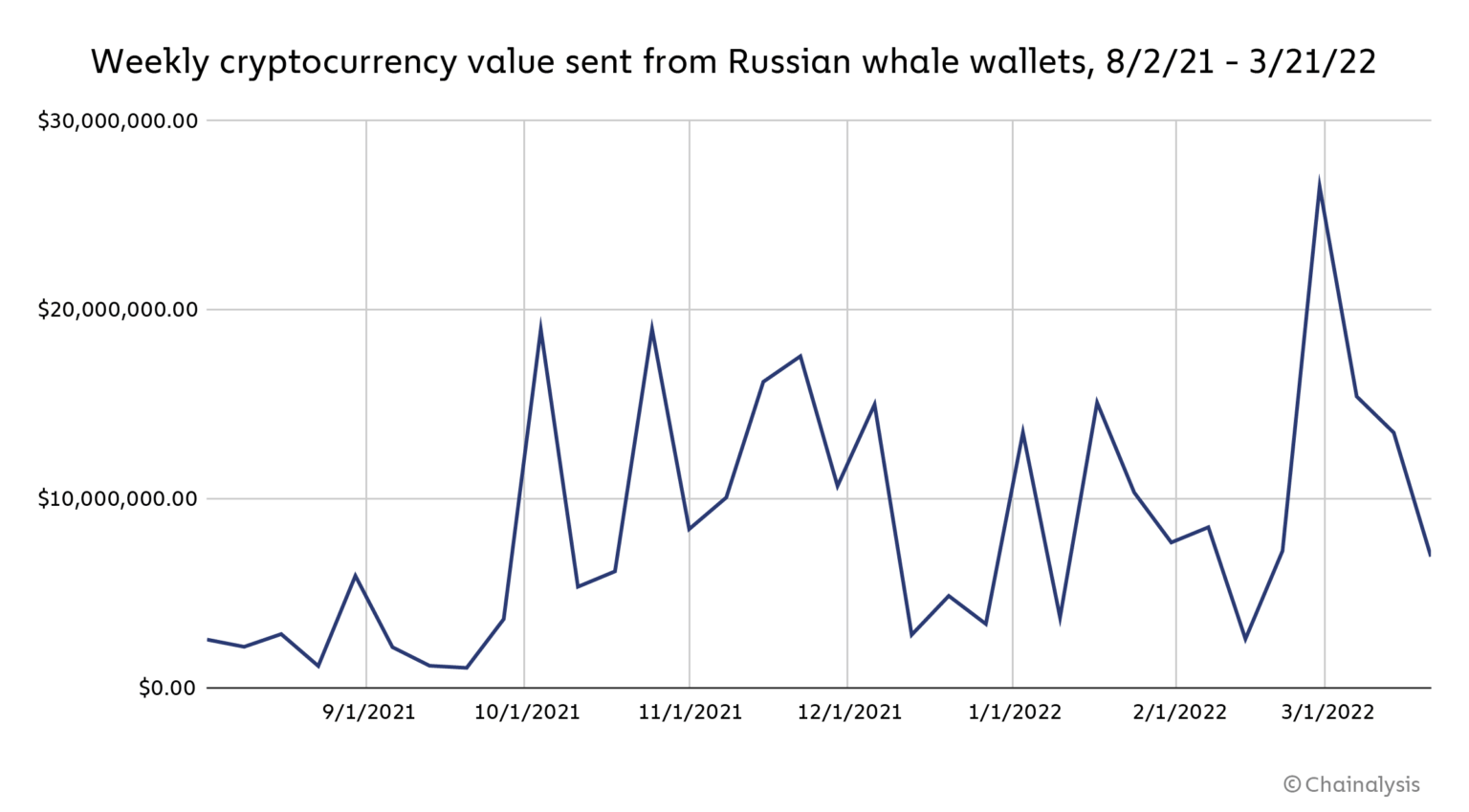

First, if Russian crypto whales – wallets with more than $1 million worth of crypto – would try to move these funds, it would show. Between the start of the invasion and the 21st of March, Chainalysis tracked just over $62 million worth of cryptocurrency sent from Russia-based whales to other addresses, many of which are associated with OTC desks and exchanges, some of them high-risk.

“While spikes in this activity are common, Russian whale sending hit its highest levels in roughly eight months during the week of February 28 soon after the invasion, reaching $26.5 million. On-chain activity alone can’t tell us if these transfers constitute sanctions evasion, as we don’t know if the whale wallets are controlled by sanctioned individuals and entities,” the report reads.

Sbercoin to zero

Chainalysis also looked into the newly created cryptocurrency issued by Russia’s biggest bank Sberbank, which was put on the sanctions list at the beginning of the war. The Sbercoin, as it is named, had previously been announced in late 2020.

According to CoinMarketCap, Sbercoin has seen roughly $4.5 million in total transaction volume, all on one popular decentralized exchange. Sbercoin’s price has dropped over 90% since its launch and currently sits at $0.00003329 as of March 28, 2022, with a market cap of $113,089. Sbercoin is thus obviously not used for sanctions evasion.

Chainalysis also looked at other cryptocurrency services and usage typologies that could indicate sanctions evasion by Russian entities, but so far, on-chain indicators for these don’t show much out of the ordinary.

Russia has a large ecosystem of services, and it’s reasonable to expect that sanctioned Russian entities may try to use these services to evade sanctions by moving their wealth through them.

No exchanges have shown any unusual activity

Furthermore, Chainalysis analyzed high-risk exchanges, those that tend to have lax compliance requirements, like Garantex and Bitzlato, which are prominent in Russia, but also Tornado, an Ethereum mixer. Thus far, none of these services have shown spikes in inflows or outflows, or any other unusual activity. Chainalysis also looked at Hydra, by far the world’s largest darknet market, with the same result.

“We are continuing to monitor Hydra, but so far, its transaction volume shows nothing out of the ordinary, and in fact has fallen in the time following the Ukraine invasion,” the report says.

Some sanctioned countries, like Iran, have turned to crypto mining to gain access to capital and make up for sanctions-related losses. It’s possible that Russia could do the same. As of August 2021, Russia ranked third worldwide in the share of global hashrate for Bitcoin. While there has been an increase in electricity consumption by cryptocurrency miners in some parts of Russia after the invasion, it’s since impossible to tell if any of that can be attributed to a sanctioned entity.

It would also be unlikely, Chanalysis writes, for a sanctioned entity to have set up a significant mining operation in the weeks that have passed since new sanctions were handed down.

Ruble trading pairs grew over 900%

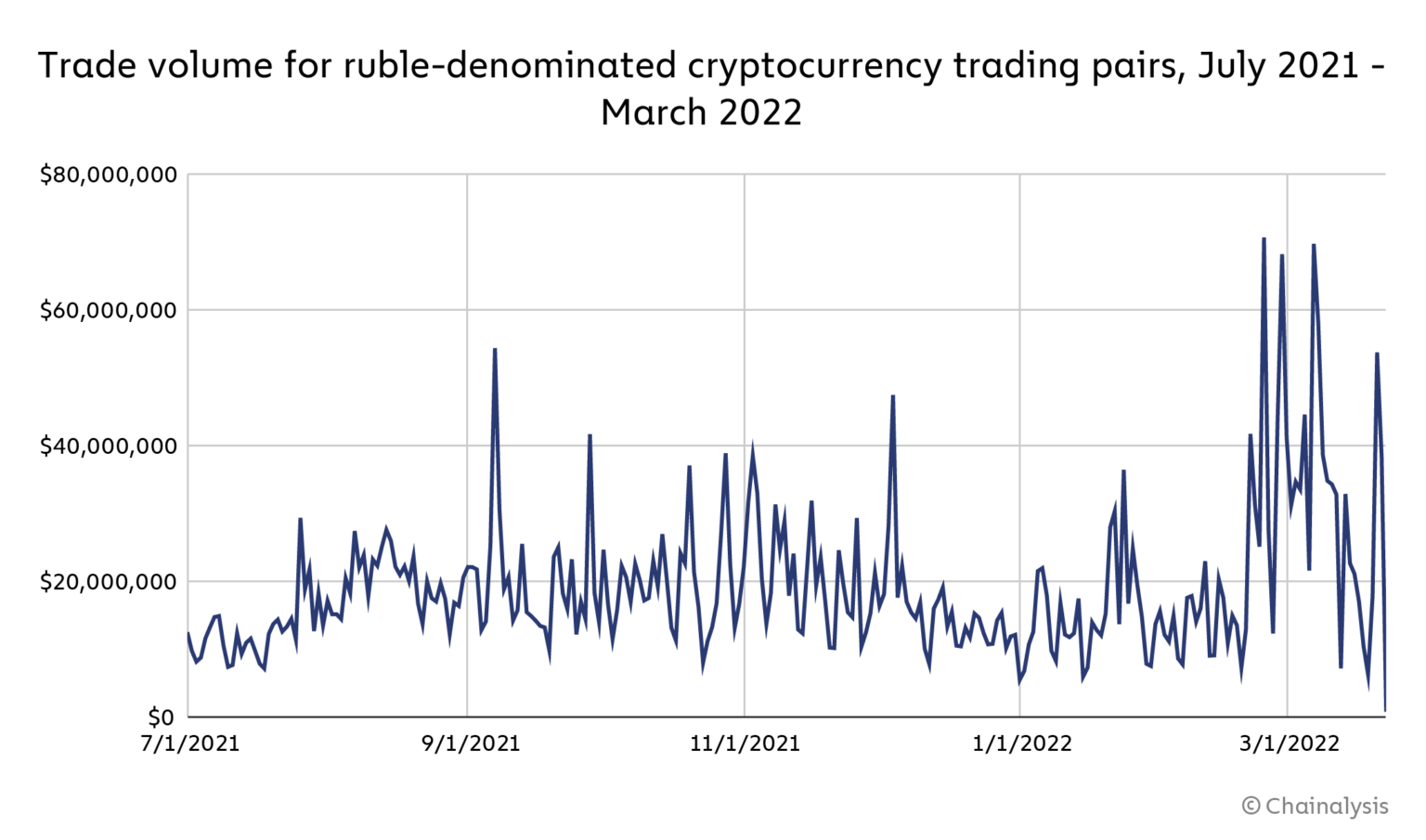

Furthermore, Chainalysis, using exchange order book data provided by Kaiko, also watched for changes in trade volume for trading pairs that include the Russian ruble. Trade volume involving ruble trade pairs increased immediately following the invasion, growing over 900% to over $70 million between February 19 and 24, the highest trading volume since May 2021.

Since then, ruble trading volumes have continued to be volatile, though they have yet to break above $70 million again. As Chainalysis previously stated, they believe this activity is unlikely to reflect large-scale sanctions evasion.

“Our current hypothesis is that the chief drivers of ruble pair volumes are volatility and non-sanctioned Russian cryptocurrency users attempting to protect their savings as the ruble’s value plummets,” the report reads.

Finally, Chainalysis also monitored activity by Russian cybercriminals, in particular gangs engaging in ransomware attacks. One of these gangs, Conti, the most active ransomware group of 2021, according to Chainalysis, declared its loyalty to the Russian government shortly after the invasion, promising to launch cyberattacks against Russia’s enemies.

Soon after, an unknown party retaliated by leaking sensitive information on Conti, including the group’s internal chat logs, source code, and more. To conclude, Chainalysis has found no sign of increased activity by these gangs, nor any activities that could indicate sanctions evasion.

$56 million worth of cryptocurrency to Ukraine

In summary, Chainalysis can’t find any significant signs of sanctions evasion. The role of cryptocurrencies in the war in Ukraine must instead be that of a vehicle for support of the Ukrainian war effort and the country’s people.

“As of March 28, crypto enthusiasts around the world have donated over $56 million worth of cryptocurrency to addresses provided by the Ukrainian government, not to mention hundreds of NFTs and donations to other charitable organizations accepting cryptocurrency,” the report reads.

“Those donations stand not just as an example of the community’s generosity, but also of cryptocurrency’s utility as a cross-border value transfer mechanism in a time of emergency,” Chainalysis concludes.

CoinGlass

CoinGlass

Farside Investors

Farside Investors